- Home

- A-Z Publications

- Animation Practice, Process & Production

- Previous Issues

- Volume 1, Issue 1, 2011

Animation Practice, Process & Production - Volume 1, Issue 1, 2011

Volume 1, Issue 1, 2011

-

-

Frame of reference: toward a definition of animation

More LessBy Brian WellsSome animation scholars assert that framing animation in a formal definition would necessarily impose intellectual limits on inquiry, while others contend that any definition wide enough to encapsulate the full gamut of ‘all things animated’ must be too wide to be meaningful. International organizations of animation ‘experts’, who have taken on the responsibility of helping humankind to understand animation, fare poorly in terms of their commitment to the pursuit of a definition, citing ‘too wide a range’ of things qualifying as being animation, and that forcing a definition could create dissonance within the animation community of scholars. Despite being experts however, the group will not formally say what properties or commonalities unite the things that they consider to be animated. After a pointed and persistent effort at uncovering a definition through spirited queries and dialogue with these groups of animation experts, I was left with many unanswered questions. Why don’t international organizations of animation scholars believe that a definition of animation is necessary? Is a definition of animation necessary? If these organizations of animation scholars cannot define animation, who can? Who will? If an ‘animated thing’ is part of a distinct group of ‘things that are animated’, then what are the properties of the thing that makes it a part of the group of ‘animated things’? Moreover, who would benefit from a definition of animation, and who would not? The purpose of this article is to explore and discuss some of these questions, in the hope that knowledge and understanding will result from the central question: what is the core set of properties that makes a thing ‘animated’?

-

-

-

Out of the trees and into The Forest – a consideration of live action and animation

More LessBy Piotr DumalaThis is a highly personal consideration of my role and identity as a film-maker delivered at the Holland Animation Film Festival in Utrecht 2010, focusing on some of the formative influences I drew from ‘live action’ film, and took in my long-established practice as an animator and animation film-maker. Both the philosophic and technical understanding of the work of, among others, Ingmar Bergman enabled me to both think about and engage with animation in a hopefully distinctive way, an approach that I wanted then to readapt back into my own live-action feature, The Forest, and a reworking of one of my earlier animated films, Crime and Punishment. This highlighted the particular place of the animator in the process and the degrees of control and choice in creating specific kinds of imagery, and the ways that it was possible to transfer life, motion and thought between forms.

-

-

-

Poetics and public space: an investigation into animated installation

More LessBy Rose BondWe live in a society not only dominated by the screen but increasingly colonized by multiple moving-image ‘screens’. This article investigates aspects of the phenomenon of viewing multi-channel animated work that coexists with architecture. Referencing historic projections, such as Glimpses of the USA by Charles and Ray Eames (1959) as well as my own animated installations, I raise questions on how the brain may be processing multiple images and explore the concept of light in a window from the perspective of Gaston Bachelard and Thomas Kincaid in order to suggest differences between projecting on or projecting from – a difference between emanation and reflection. The article closes with brief thoughts on the window – illusion and collapse of 3D space, the image and the archetype and the idea of spectacle with content.

-

-

-

Emptying frames

More LessThis short essay brings together some thoughts about two films, both of which take as their starting point the photographic still image and use film to expand and question the immobility of that image, teasing out small shifts and changes in its appearance. Candle and Tidal combine 16mm film and Polaroid photography to create a metaphor for movement and loss, evoking the alchemy of the photographic as it becomes a memory in a digital age. Through a commentary and reflection the formal characteristics of the work are described, and I explore how the filmed Polaroid is animated by the chemical transformation inherent in the Polaroid process. One of the key points is how the films concern themselves with articulating the filmic interval, as a chemical manifestation/metaphor.

-

-

-

Animating by numbers: workflow issues in Shane Acker’s 9

More LessThis is a short overview of Starz Animation’s production process for Shane Acker’s debut animated feature, 9. The film was challenging to make because it was done on a small budget and a limited time frame and required a high degree of invention and creativity to address the issues raised without compromising the quality of the film. The piece details some of the ways in which we approached problems, and how we developed solutions, especially in relation to character design, art direction and workflow in the production pipeline. It seeks to offer an insight about a smaller studio seeking to make a ‘Hollywood’-style animated feature that can stand up against the work of major studios like Pixar and Dreamworks, and also find a crossover audience in art cinema and festival circles.

-

-

-

In visible hands: the work of stop motion

More LessThis essay puts artists, historians and theorists into conversation with each other in the context of an examination of stop-motion work process. Stop-motion film-makers frequently blur the boundaries between work and play as they practise their painstakingly labour-intensive craft, and this essay considers how the work of the animator’s hands is evoked (in implicit and explicit ways) in two key examples of late-twentieth-century stop-motion film. Starting with Adam Smith’s metaphor of the ‘invisible hand’ as a figure for self-regulating tendencies within capitalism, and extending into far more critical re-examinations of the figure by C. Wright Mills, I discuss the visual culture of workplace efficiency analysis and its relationship to the history of stopmotion film. I focus in the remainder of the essay on representations of work process in Henry Selick’s Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas and Peter Lord and David Sproxton’s Confessions of a Foyer Girl. I argue that these films’ contrasting considerations of work are enmeshed within ambivalent considerations of the political economy of cinematic production and distribution.

-

-

-

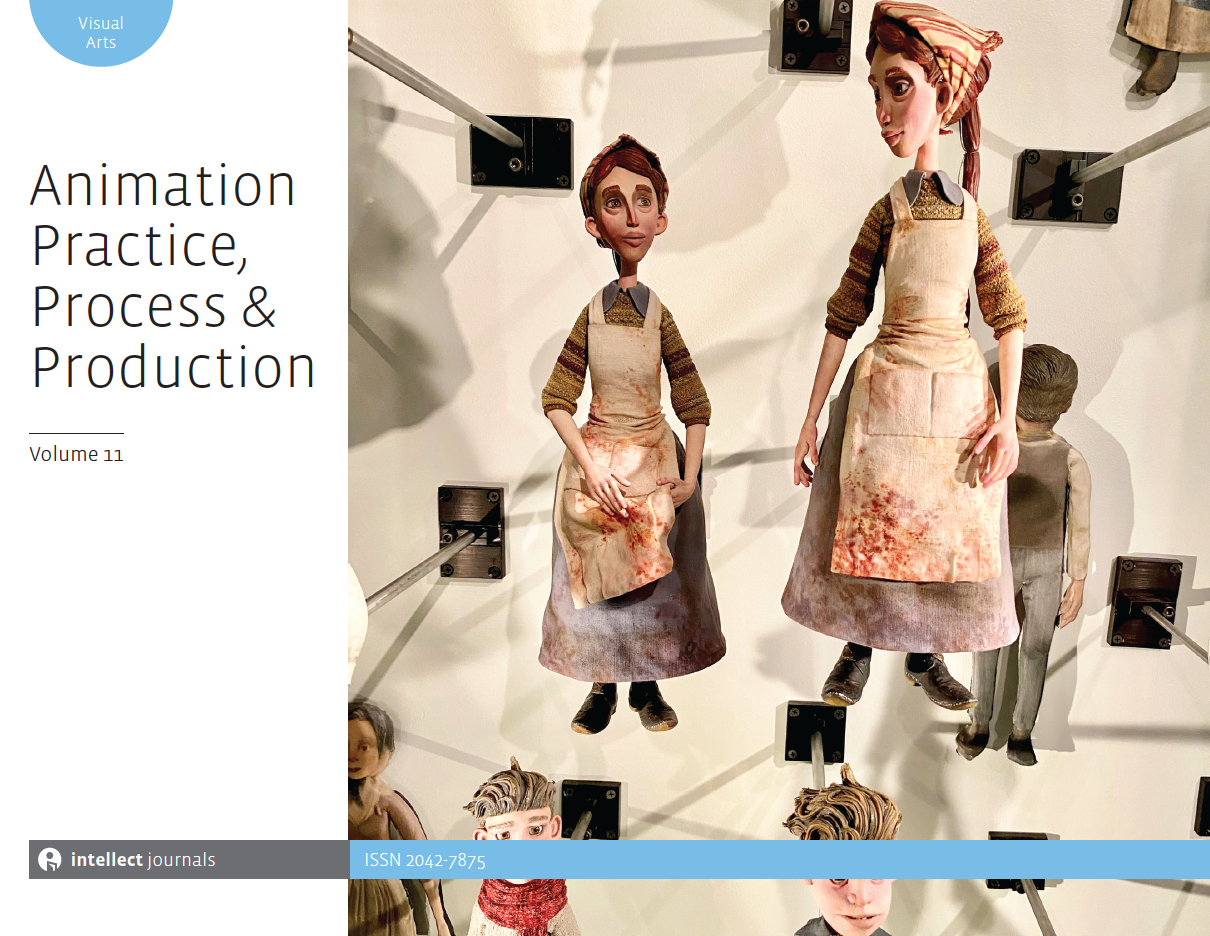

Searching ‘In the Attic’: a visual production diary

More LessBy Jiri BatraThis is a visual essay recording the production process of a 75-minute stop-motion feature animation, made in the spirit of traditional Czech puppet animation, but using mixed media techniques. It is a story called In the Attic: Who Has a Birthday Today? and though it is a children’s animation, based on the way children conduct their games and imagine their play environment, it is also a political metaphor, reflecting upon past Czech history. The images in the essay show different aspects of production and reveal some of the approaches taken to achieve certain craft effects. The film includes puppet animation, clay animation, cut-out animation and drawn animation; and uses post-production tools, but has no computer animation.

-

-

-

Anthropophagy and anthropomorphism: constructing ‘Post-Colonial Cannibal’

More LessIn the 1930s and 1940s, a popular genre of animated film emerged in the United States – the ‘cannibal cartoon’ – in which the anthropomorphized ‘white hero’, marooned on an island, was captured by a tribe of savage cannibals and thrown into the cooking pot. London-based comic art project Let Me Feel Your Finger First are designing a new animated character – ‘Post-Colonial Cannibal’ that makes reference to – and challenges – the depiction of ‘the savage’ in these early animated films. This article presents and discusses some of LMFYFF’s initial design ideas and examines two examples of the cannibal cartoon, Ub Iwerks’s Africa Squeaks (1931) and Walt Disney’s Trader Mickey (1932). Focusing on the animators’ visualizations of the cannibal king, the cannibal tribe and the anthropomorphized ‘white hero’, the article identifies particular components of the animators’ designs and considers the coded meanings contained therein. LMFYFF reflect on the influence of blackface minstrelsy and consider the cannibal’s place in animation’s ignoble history of racial stereotyping. And LMFYFF pose Post-Colonial Cannibal’s implicit question: how can a medium that has historically depended upon caricature – with its accompanying modes of simplification, exaggeration and distortion – represent otherness?

-

-

-

The Dutch Animation Collection: a work in progress

More LessAuthors: Mette Peters and Peter BosmaDutch animation film has a history that goes back to the first decades of the twentieth century. Over the course of this history many Dutch animation film-makers have been internationally successful; their work has been shown at major festivals and they have received many awards. This text observes that many of these films became unknown for contemporary audiences. The situation of the Dutch animation heritage will be investigated in more detail, and touch upon the contemporary position of animation film in the field of preservation and film archives in general. The focus of the text will be the practice of a research project initiated by the Netherlands Institute for Animation Film (NIAf) that intends to enhance the safeguarding of Dutch animation, and by doing so making films accessible and available for research and public presentations.

-

Most Read This Month