-

oa Senegal

- Source: Global Hip Hop Studies, Volume 3, Issue 1-2: Hip Hop Atlas, Dec 2022, p. 97 - 105

-

- 30 Jan 2023

- 31 Jan 2023

- 20 Dec 2023

Abstract

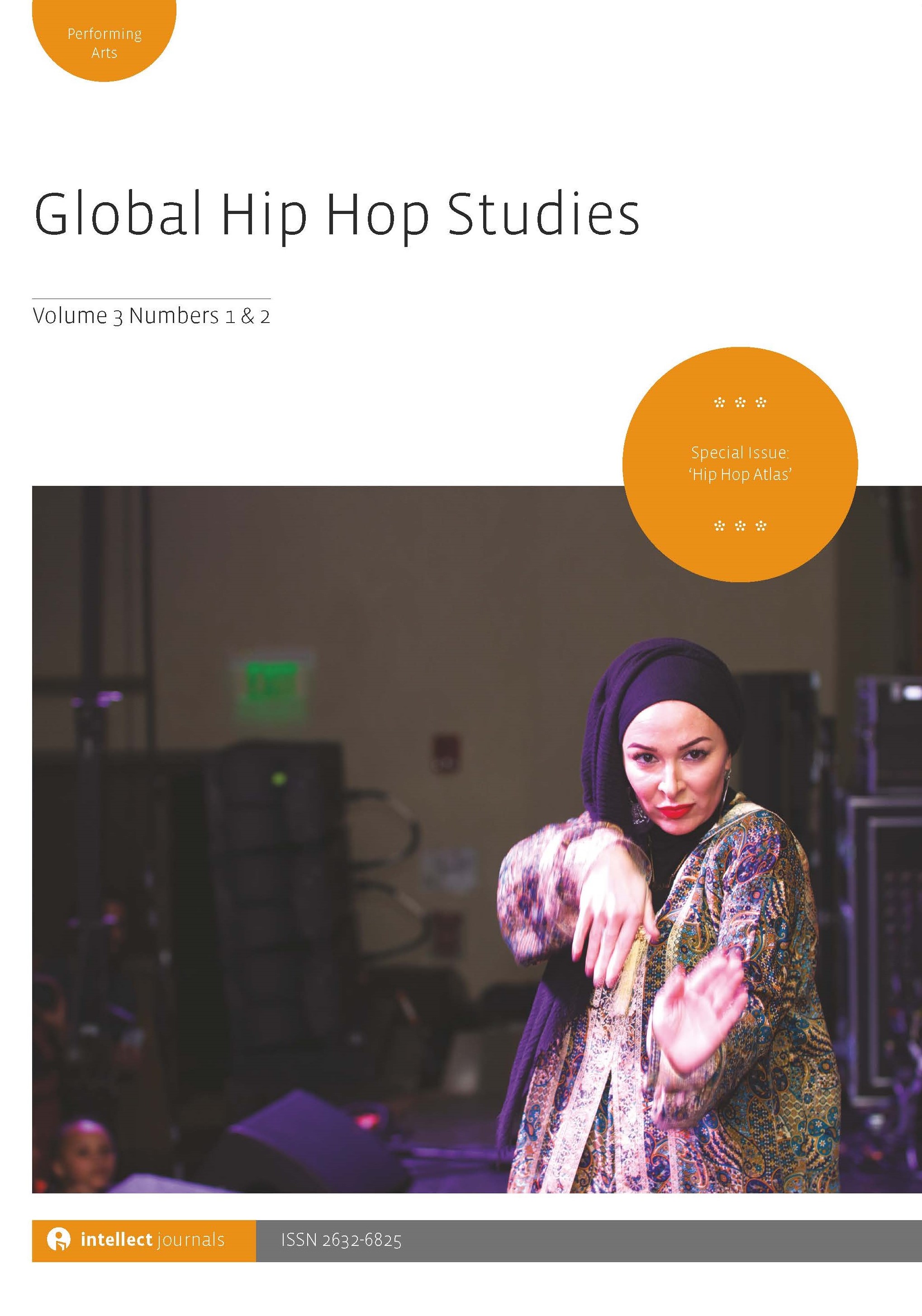

In 2018, Senegalese hip hop celebrated its thirtieth anniversary as one of Africa’s most vibrant hip hop scenes. Senegalese rap has asserted itself not only as an expedient form of urban art, but also as a socially, politically, and culturally powerful instrument of both persuasion and mobilization for the masses. From its privileged beginnings in Dakar’s posh nightclubs and Catholic high schools, the genre soon asserted itself as quite distinct from hip hop in other parts of the world, and its popularity increasingly grew to wide segments of the Senegalese public. From the mid-1990s, the underprivileged segments of the society (especially those from the poor peripheral neighbourhoods of Dakar) became progressively vocal, using hip hop as an instrument to give voice to the economic and political predicaments of the people, particularly the youth. The production of the music became increasingly local, and its primary language the Senegalese lingua franca Wolof. What has given Senegalese rap both its personality and power, while enabling it to keep an international aura, has been its political engagement: from early on, Senegalese hip hop has been strongly penetrated by politics and the denunciation of the living conditions of the population, of political abuse and social inequality. This article examines ‘hip hop galsen’ over three decades, detailing its development as a successful genre grounded in local realities that gives voice to the concerns and predicaments of the Senegalese public. It concludes through an examination of recent changes, as evidenced in new musical influences, the several important female voices that can now be heard within a historically male-dominated genre, and the greater support and acceptance hip hop has recently enjoyed, equipping the current generation of Senegalese rappers with the promise of bringing it to the international stage.